By E. Richard McKinstry with assistance from Jim LaDrew and Judy Ng

John T. Chambers, known familiarly as Uncle Jack, was born on March 11, 1842 in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, the youngest of thirteen children, to John Pusey Chambers (1791-1870) and Hannah Thompson Chambers (1799-1873). In 1870, he married Alice E. Jackson (1847-1927) and together they had two sons, John T. Chambers, Jr. and Cyrus Stanley Chambers, and one daughter, Mrs. Rosamond Chambers Trump, who eventually resided in Syracuse, New York.

Chambers was principally a farmer, and he also worked for the Westinghouse Company installing railroad signals, including the first signal system at the Broad Street station in Philadelphia. In addition, in the 1860 federal census, his occupation was listed as an apprentice machinist; in 1900, he was a boarding house keeper.

A Quaker and a member of Kennett Square’s State Street Meeting, despite his religious affiliation, Chambers also served in the army for three years during the Civil War as a member of Company A, 124th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers. In 1862, he took part in the Battle of Antietam, and shortly after being commissioned as a Major in 1863, he was wounded in the left hip at the Battle of Chancellorsville. A veteran, Chambers was an active member of the McCall Post of the Grand Army of the Republic.

Chambers’ obituary in the Kennett News and Advertiser pointed out that he was “an entertainer of no mean ability; a sweet singer who also accompanied himself on the guitar, and was the life of social gatherings. It was he who introduced the song: ‘Tenting Tonight on the Old Camp Ground.’” In 1932, Chambers died at his home, “Bloomfield,” in Kennett Square. He and his wife are buried in Longwood Cemetery.

On the 58th Anniversary of the Battle of Antietam, Chambers wrote the following letter describing his memory of that battle and his Civil War experiences. The original letter can be found in CCHC’s Civil War Collection.

Kennett Square, Pa. Sept. 17, 1920

Dear Howard,

Under another heading, I answer as well as I can about heraldry. As I have a little time left before I start for the reunion of 124th Regiment at Chester on this the 58th Anniversary of the Battle of Antietam, Maryland. September 17, 1862, that day of slaughter, when every fifth man engaged was killed. 34,360 were left dead in a little less than eight hours, from dawn to 1:30 pm. 170,000 engaged (90,000 Union, 80,000 Confederates). I was a Private there and my position was in front line in Company “A.” My bunkie, Austin Collen was killed on my right, George McFarland on left. And Sargent John Windle in the rear were wounded.

About 10 o’clock our battle flag was captured by the Lone Star of Lexington.

We would not stand for that and charged bayonets, got our flag and took theirs, which we retained and brought to Harrisburg with us. We made many charges before we got through. We took one prisoner in our _______, a Georgian man. We gave him the best we had, yet seemed down-hearted, so I asked him what was the matter, was he not glad he was a prisoner? His answer was he wanted to write home before he was shot. In surprise, I asked him what he meant.

He said, “ain’t I to be shot?” “No,” I told him he would be cared for and probably paroled or exchanged, after a time. “My God, if weins knew this, we would all be over here. We were told we would be shot.” He was sent to Johnston’s Island, Lake Erie. We spent the night looking for our comrades and caring for the wounded and writing to their families at home by the light of pine torches. An awful night for us as we had little to give the poor fellows but water, which was the first thing wanted by the wounded. We had nothing to eat for 48 hours.

As I have gone this far in my story of Antietam, I am tempted to begin at the beginning of our experience. August 1, 1862 (after being in camp since April 21, 1861). We were put into the 124th and sworn into U.S. service and sent to Alexandria to build forts. On August 28th (’62) we heard heavy firing toward Manassas (Bull Run). We were ordered double quick for seven miles, and met our Army in full retreat. We joined in the retreat back to Alexandria. McClellan there was ordered from the peninsula (James River) and we were joined with his army, making 90,000. Then we started on 300 mile march (13 days) in a horse shoe curve covering Washington, Baltimore, etc. along Pennsylvania line. Our next battle was Chantilly, one of Robert E. Lee’s old homes. We were not called into firing line. Then we came to the Monocacy River which we forded neck deep, into the town of Frederick, on Saturday September 12th, ’62 and camped on Stonewall Jackson’s ground which he had vacated a day or two before. We rested Sunday. Monday morning we were again in motion, and in passing down the street of the little town, we were showered with fruit and flowers. We passed a small white house. In the doorway stood a woman about sixty years old, waving a Union flag. We were told this woman (Mrs. Quarautal) waved this flag in the face of Johnston’s army a few days before, and he was noble enough to forbid firing. This was the incident, the theme of Whittier’s “Barbara Frietchie.” It did not make much impression on us. We did not know we were making history. The house has been torn down and a bronze tablet marks the spot. Late in the afternoon, we struck Jackson at South Mountain, 4 miles from Frederick, too late for action before the Johnnies quit. The first dead man we saw here was General Reno, formerly of Chester County, Commander Union troops. We lost 6,679 (both sides) there.

The next morning we started in hot pursuit of Jackson, toward Sharpsburg, Virginia and came near Antietam Creek about 10 p.m. About midnight we crossed over, and formed line battle near Miller’s Spring. Just as day dawned on morning of the 17th the battle opened. Colonel Hawley was the first to fall. A sharpshooter got him in the neck. The ball was never removed, and he carried it to his grave 50 years after.

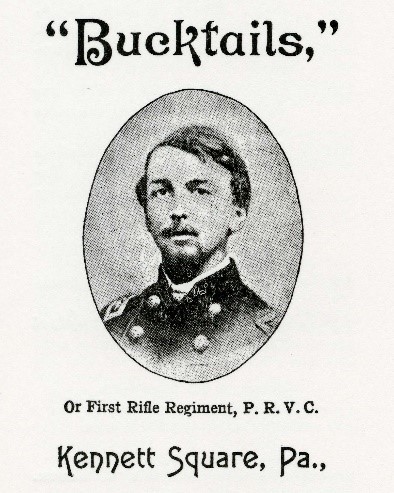

After Antietam, the Army was reorganized. McClellan was deposed and Burnside placed in command. Kane the old “Buck Tail” commander was made Brigadier General. The 124, 128, and 130th Pennsylvania made up his brigade (3,000). Our old captain, Fred Taylor was made Colonel of the old Kane “Buck Tails.” General Thomas L. Kane was a brother of Dr. Elisha Kent Kane, of Arctic fame, who went to search for Sir John Franklin in the early ‘50s. General Kane was a West Pointer and went to France to study war. Soon he decided to introduce the bugle drill. Then trouble began. The bugles would sound the order and neither officers or men knew what they meant, and as there were 60 calls, it was confusing

It will be necessary to go back a little here in personal matters. Just before Antietam our drum major died. Hawley sent for me to come to headquarters. I was wondering when I had disobeyed camp duties.

He said, “Chambers, I want you to be drum major.” I told him a drum and I were total strangers. “No matter, you know the drills, and musical besides. You will be relieved from picket and guard duty, but will be required to serve in the ranks.”

As I did not like the lonely picket stint, I accepted. When the bugle racket came about, Kane sent for me and said, “As the bugle calls are a blank for the men, I will translate the French words and appoint a man from each regiment to learn and sing the calls in camp, on drill, and march, and you are appointed from 124th as one of the brigade singers.” It was not long before we could drill by bugle. I was not obliged to carry a rifle but told him I preferred to stay by the boys, so got permission to do so.

After we had buried and burned the dead on Antietam and looked on 10,000 arms and legs piled up like cord wood, front of the old Dunker Church, we moved to Maryland Heights overlooking Harpers Ferry and went into camp.

In a few days we were visited by the battle plague, which the doctors called black measles. Strong men would go to sleep, and be carried out dead, in the morning, as black as a negro. Panic reigned for a time so we moved camp, crossed Potomac on pontoon bridges, forded the Shenandoah then over Loudon Mountains and camped on the “Wheatland Farm.” Here we built mud huts, as our tents had been taken from us for some reason, and had to take the open as we found it. J.B. Stuart, the Confederate cavalryman, gave us trouble, raided our camp and the Shenandoah Valley. Burnsides put us on the march to rout him. We came to Goose Creek. Here we saw the only cavalry fight of the war. Stuart and Phil Sheridan came to an agreement. Each had 1,000 men and for one hour fought with saber, not a shot was fired. The infantry was halted, so we had a full view of the action. Stuart quit.

This was in front of the little Quaker church at “Goose Creek.” We went over to Leesburg, had a scrap. We lost no men in our brigade, then returned to Wheatland and were not molested but once, at Kane’s Landing on Potomac, night attack, raided our huts. None killed and but few wounded.

On 14th January ’63 in miserable cold rain, we were started for Fredericksburg. Mud up to the axle of cannon. 8 horses to a gun, when it is a full team. We marched hard till 4 p.m. and made 4 miles. Wet to the hide, a long struggling Army, fully disgusted with army life at 7.00 per month in greenbacks with gold at 2.85 (afterward raised to 13.00 per month).

We came to an impassible stream. Burnsides called McGregor, general of _______ to his aid, asked him to build a bridge saying he would send to Washington for plans. In disgust McGregor turned away and in the morning reported the way was open. But “the picture had not come.”

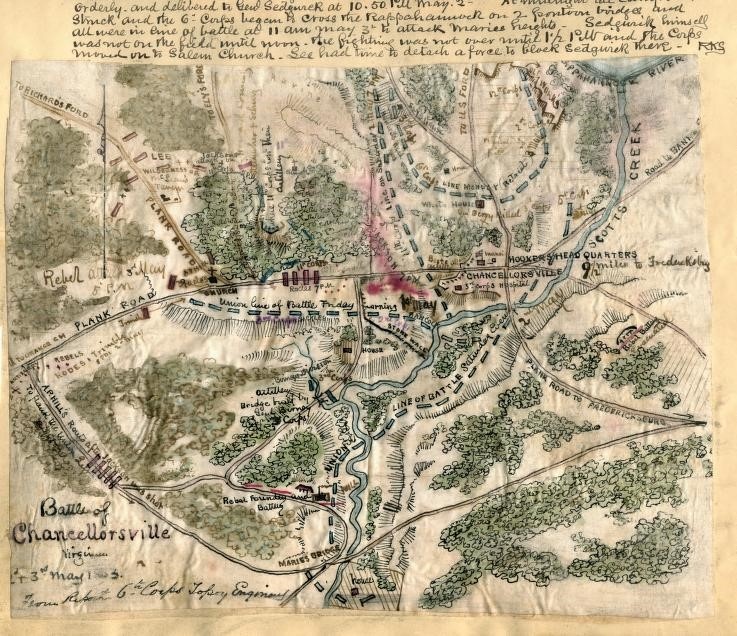

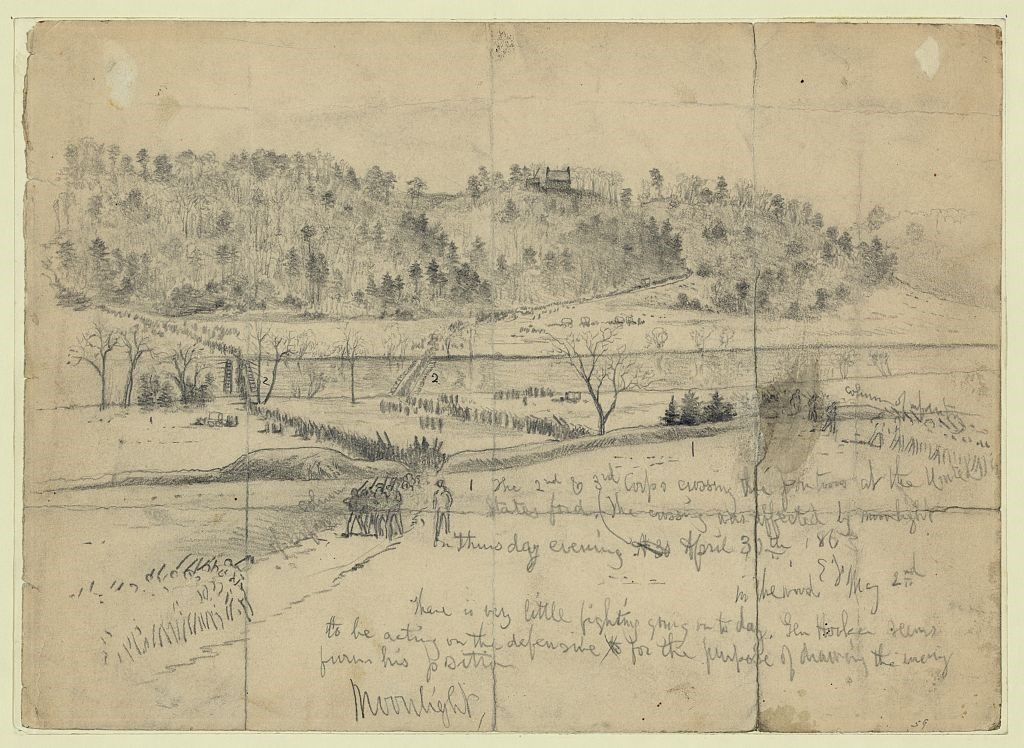

The Irishman was practical. Burnsides, as he called him, “fuss and feathers.” After another day of mud marching we came to the Rappahannock, opposite Fredericksburg, and saw a large sign on west side of the river which read “Burnside’s stuck in the mud.” We could not bring on a fight on account of the condition of roads, as we could not get our guns up, and ammunition, supplies. So we marched back to the Potomac again and went into camp at Aquia Creek on the Aquia Creek Fredericksburg Railroad where we could get supplies via water (this was called “Burnside’s Mud March”). Here we camped until April 14th and again started for Fredericksburg. Burnside was deposed and Joe Hooker came into command. We bumbled around until April 27th, then under cover of fog and rain marched up Rappahannock to _______ Ford. Found the river in flood and could not ford. Halted two hours and built bridge of pine trees. When we started we changed front. The 11th Corp (Segal’s) took the lead and we, the 12th Corp, came next.

The bands of the 11th Corp began to play “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and the 20,000 men of the 11th sang as they marched along. The grandest thing in music I ever heard. We did not understand the words as the 11th was a German organization. The morning after crossing, the battle opened. The battle ground was the “Wilderness” and the only open space was the old “Camp” plank road, leading from Washington to Richmond. After fighting all day, we were driven back to the river. The next day was a repetition of the same. So it was until May 1st. The time of the brigade (Kane’s) was then up (9 month men). Kane stepped out in font and said, “Boys, your time is up today and you can go home if you wish, but you see how we have been fifty-three days, and licked every day. We need all the men we can get. Will any of you re-enlist? If so, please step out one step.” The whole 3,000 stepped out. “You misunderstand, this is a re-enlistment. Now, will any come forward?” And every man came to the front. “Alright boys, I am proud of you. Fall in and we will see this through.”

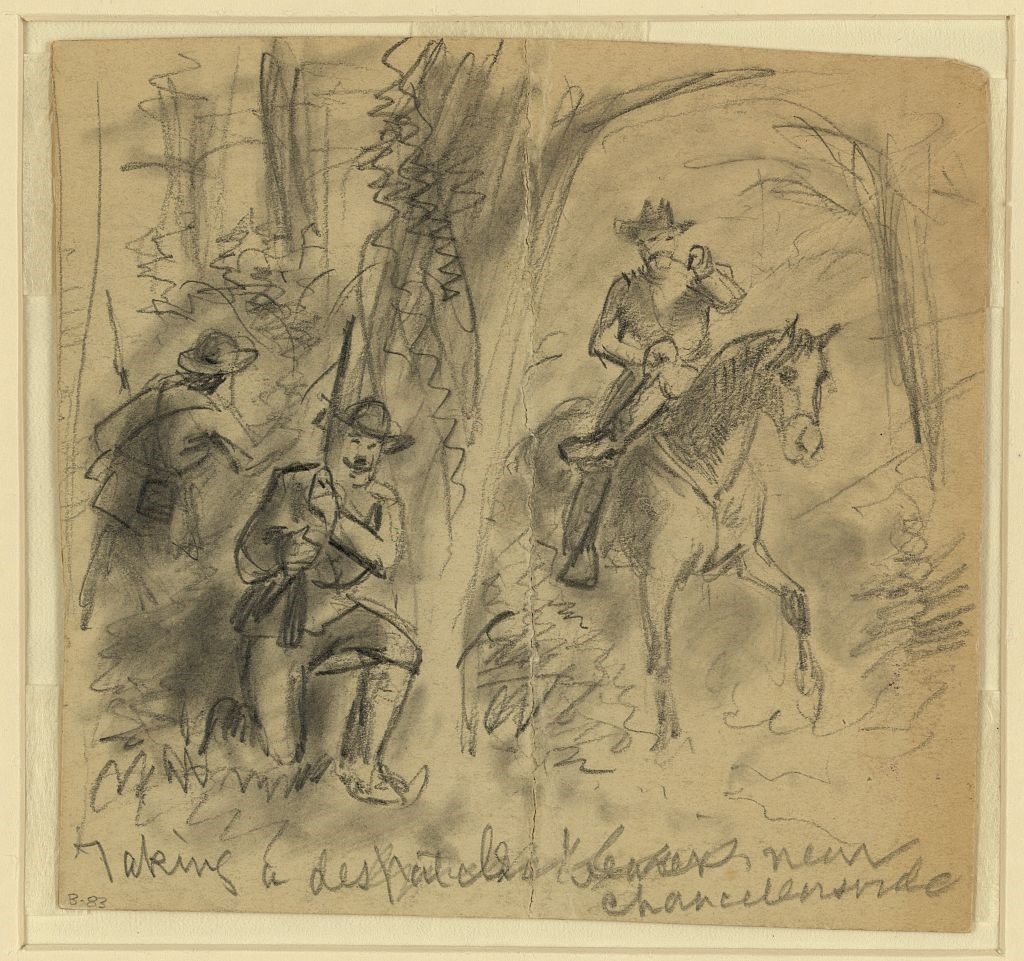

This was what I call patriotism. These boys, tired, dusty, hungry, homesick, and lousy, sticking to “Old Glory.” I was promoted to Major, provided with a fine horse, and assigned to courier duty, to carry orders from headquarters. I had many narrow escapes.

On the morning of 4th May, just as I was taking order to Kane, a percussion shell exploded between his horse and mine. He went down, but none of [the] pieces got us. I returned to regiment to ____ just in front of the old Chancellorsville Hotel. Jackson’s army had us surrounded (in a clearing) so the brigade formed back to back, which threw us (some officers) in front of our own rifles. I laid down and the boys fired over us. In a few minutes I got a Minnie ball through [the] left hip. The bugles sounded “fall back.” I did not fall back, and looked for a trip to Libby, with some other comrades who had been captured.

Three of my comrades came after me under heavy fire. They were Ed White, Ed Davis, and Ed Strong (the three Eds they were called). Don’t you think this act endeared these boys to me? They did not think of self. They carried me back to the rear of our 3’ breast works, where the doctors were at work.

While I was lying there, the Johnnies massed 24 regiments deep and charged through the bushes at the 11th Corp, which broke in wild panic. Our Corp the 12th could not stop the rush, but did not break, but fell back in good order. Pleasanton’s Pennsylvania cavalry and Doubleday’s artillery (42 guns) got into close action to stop the rush. It was a failure, and the whole army of Hooker was driven in confusion across the Rappahannock in disgust, a most disastrous defeat. I was witness to Keenan’s Cavalry charge (under Pleasanton). His command 300, charged, and not one came back.

The story is told by George Parsons Lathrop, if you have a chance some time to look the story up. You will find it in Steadman’s American Anthology, page 538. The loss was a total of 30,218 at Chancellorsville, one of the most disastrous battles of the war. All my figures are from the report of the War Office. Lathrop names the 2nd of May, it took place the 4th about sunset. The wilderness caught fire, and burned the wounded and dead.

It was a bright moonlight night. The whippoorwills, by the thousands, hooted their mournful cries, and added their doleful notes to the sound of battle. We fought all night. The Army (all that was left) marched back to Potomac and camped on our old ground at Aquia Creek.

Hooker was now deposed and Meade made commander of [the] Army of Potomac. The army was reorganized, and soon came into battle at Gettysburg July 2, 3, 4. On the night of May 4th some of the wounded were tumbled into springless army wagons, and hustled over the rough corduroy roads, back to the Rappahannock to a large brick plantation house on the west side of the river (battle side) where the doctors were at work. About midnight, I was placed on the operating table, and the verdict was a hip amputation. I said no. “Then you will die.” I felt that so severe an operation would be fatal and preferred to risk the wound. After swabbing and bandage, I was carried out and laid on the brick floor of [the] porch. About 2 a.m. a comrade blundered over me, and I asked him what he was doing. Said he was looking for a place to lie down. We got to talking and I asked him where he was wounded. Said through the head just above the eyes. I said I was something of a liar myself. “No matter I will show you when day comes.” Sure enough there was Minnie bullet hole in each temple. The bullet struck the skull, and ran from side to side just under the skin. “Don’t it hurt you?” “No, only I have a hell of a headache.” I quote this only to show the curious courses bullets make.

On the morning of May 5, a lot of the wounded were taken down river to Falmouth (opposite) Fredericksburg to load on train to Aquia Creek Sanitary Commission Hospital. The battle between Sedgwick’s division and Johnnies, on the brow of the St. Mary’s Hill, was still going on, and the Confederates opened fire across the river into the wounded. Many were killed in this way. Late in evening we reached the hospital. Here I met a comrade nurse, John Pugh of Conshohocken, who gave me special care (milk, punch, etc.). I met him again at the reunion on 19th _____. In a few days, brother James came to see me, after much bother to secure pass. He made all arrangements possible for my comfort. In two weeks, a lot of us were loaded on transports for Washington. I was put in some church station. From that time I have no recollection until I found myself in Camp Curtain (Harrisburg). I suppose the great loss of blood made my mind a blank.

I was here 4 months, until September 14 when I was permitted to go home to recover. In about 18 months [I] could get around with two legs.

During Gettysburg we could hear the roar of battle, and spent three anxious days waiting to learn the contents of telegrams, as to how the battle was going. This was my war experience in the main. I would not care to go through the hard service of Army of Potomac again. But take it all in all, it was a valuable experience. It taught us self-reliance, made us appreciate comradeship to know there was no yellow streak in them who stood by “Old Glory.” All the comrades of G.A.R. are good men and true, tied together by bonds never to be broken. You may rest assured the wearer of the little bronze button is a true patriot. If he had a bad Army record, he is soon dropped from the G.A.R. roll.

Here I want to explain how I belonged to the Buck-Tails, and yet cannot claim it is my insignia of service. On Sunday, April 21, 1861, ninety-six men (nine over twenty) of Kennett made up the “Fred Taylor Company” (only two of us left). On the following Tuesday, went into camp at Rosedale, using the old barn as barracks, and went to drilling under a West Point major, with broomstick guns.

After two months, there was a call from the “Wayne Rifles” for a commander, and forty men to fill up their company and thus complete the Pennsylvania quota of men under the call for 75,000 defenders.

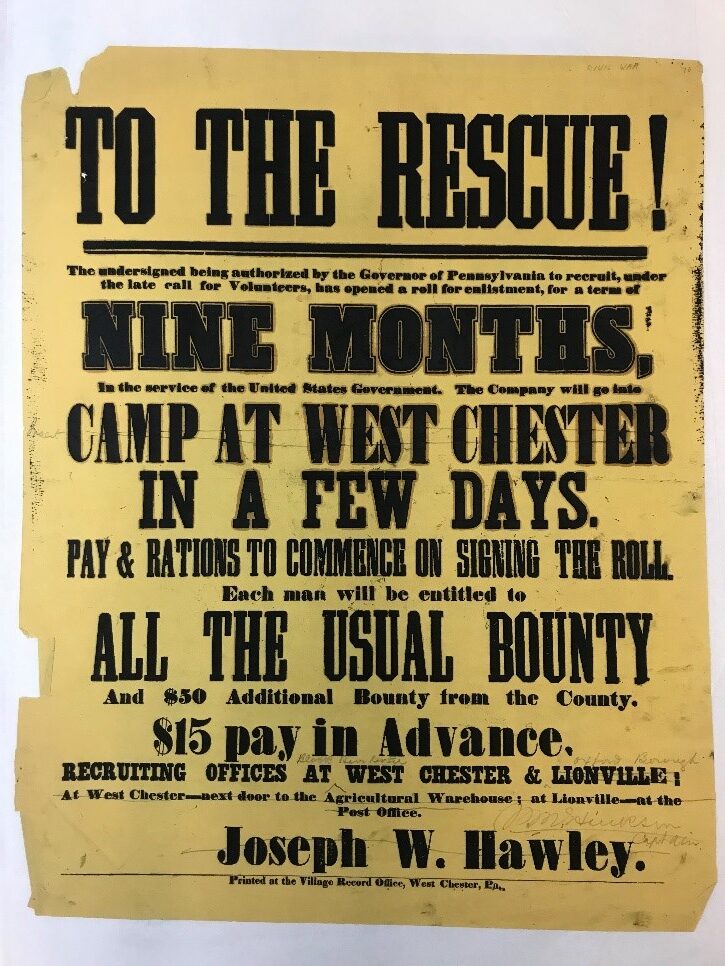

So Captain Taylor and 40 boys joined them and became Company H under Kane. The band stayed in camp and recruited and drilled a full company (100) waiting for the next call, for 300,000 which soon came. On August 1, ’62 we joined with Delaware County boys, and made up the 124th under Joseph W. Hawley, nine months men.

We did not think the war would last longer as the “store box” prophets said we could lick the rebels and “be home in time for breakfast.”

Breakfast was delayed three long years.

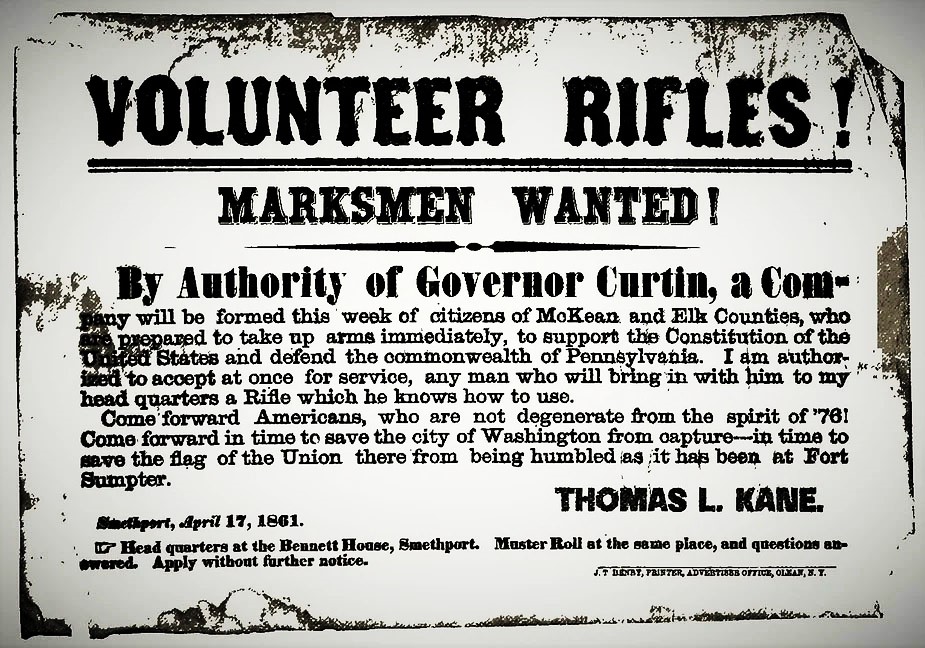

Now a little more about the Buck Tails. Kane lived in Kane, Pennsylvania. He recruited six companies from the hunters and woodsmen in the north tier of counties. As there were no railroad in that region by which they could reach Harrisburg, they built a raft, run the U.S. flag up amid-ships, nailed a buck tail on top of [the] mast, set sail down the Susquehanna for Harrisburg. After a two weeks voyage, they reported to Governor Curtin for service. They were armed with various makes of hunting rifles.

Curtin equipped them with standard arms and uniforms and they were sworn into the U.S. service, and had their first, in the first set battle at Drainsville, near Washington.

The name buck-tail originated by a comrade who while walking through a market place, cut the tail from a buck, and stuck it in his cap.

Kane at once named the regiment Buck Tails. This was the original Buck Tails, and they were imitated by others, known as New Buck Tails. Some 15 years after the war I was in a Trolley car in Philadelphia and Kane got aboard. He soon spotted me and exclaimed, “Hello Chambers.” “Why General, how did you know me?” “Know you? Why I know every man who was in my brigade.” And he named over all the members from Kennett and extended an invitation for all to come to Kane to hunt.

I never saw him again. In ’79 I was in the region of Kane (while in signal business) and took a day off to visit his grave. I placed a bunch of autumn flowers on the mound above him. He was a remarkable man, and most lovable. In speaking of Curtin (the war governor of Pennsylvania), he with Governor Andrews of Massachusetts were the strong links in the chain holding for the Union, and Lincoln leaned on them in his trials. In answer to Lincoln’s vow to God, “If the Union Army could win one important battle, he would free the slaves.” This came about after Antietam. I don’t know why I should inflict all this story on you. The first time I have written so much about my story, from my diary kept while in the service. One more incident, and I will relent. At a reunion of the blue and gray at Altoona (about 1880) a bunch of our post (Bernard Post #42) were standing at a street corner when a man in gray uniform joined us.

I noticed he had lost three fingers of right hand when he saluted us. I said, “Hello Johnny, where did you leave your fingers?” “At Chancellorsville,” he said. “Are you the man who shot me?” “I don’t know. What struck you?” “A Minnie ball put me on the toboggan.” “Oh no, it was not me. Had I struck you, I would have knocked your d—-d head off. I was in the Artillery. What part of the woods were you in?” “In a small clearing, front of the old tavern (Chancellorsville House) in a battery under Longstreet. On the afternoon of May 4th, 1863, we had Kane’s brigade in a trap and about to capture the whole command, when a battery of regulars (U.S.) came to their assistance and the Yanks got away.” “Where were you at the time Stonewall Jackson was wounded?” “I was not 100’ from the spot.” “How did it happen that a commander would be wounded, so near the front?” “He went to reconnoiter, and his own men mistook his party as Yanks, and fired, giving Stonewall a mortal wound.” We know his story was true, as it was just as he told it. We knew of [the] incident almost within the hour.

Jackson was an honorable fighter, came out in the open as a rule, seldom used the bushwacker tactics. I have read this wild ramble over and almost tempted to throw in waste basket.

Truly Yours,

John T. Chambers

[post script]

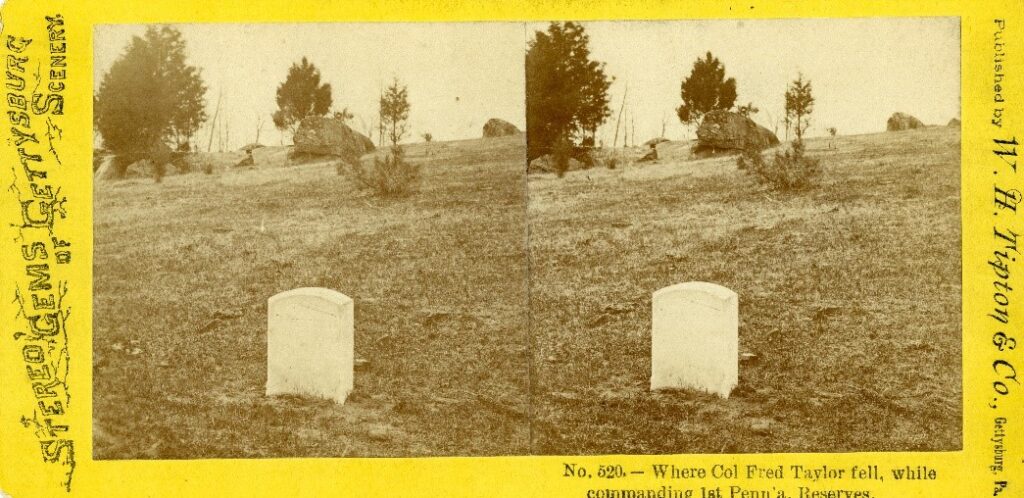

Fred Taylor was shot through the heart in the peach orchard at foot [of] Little Round Top (Gettysburg) in July 3, 1863 just as he called, “Come on Buck Tails.”

He was a boyhood companion and we all loved him as a commander.

You will notice I have named May 4, 1863 as one day full of business. It sure was an anxious horrible day.

- Photo of Ruth, Alice, and John T. Chambers, Bloomfield: The Chambers Homestead at Kennett Square, PA, 1920

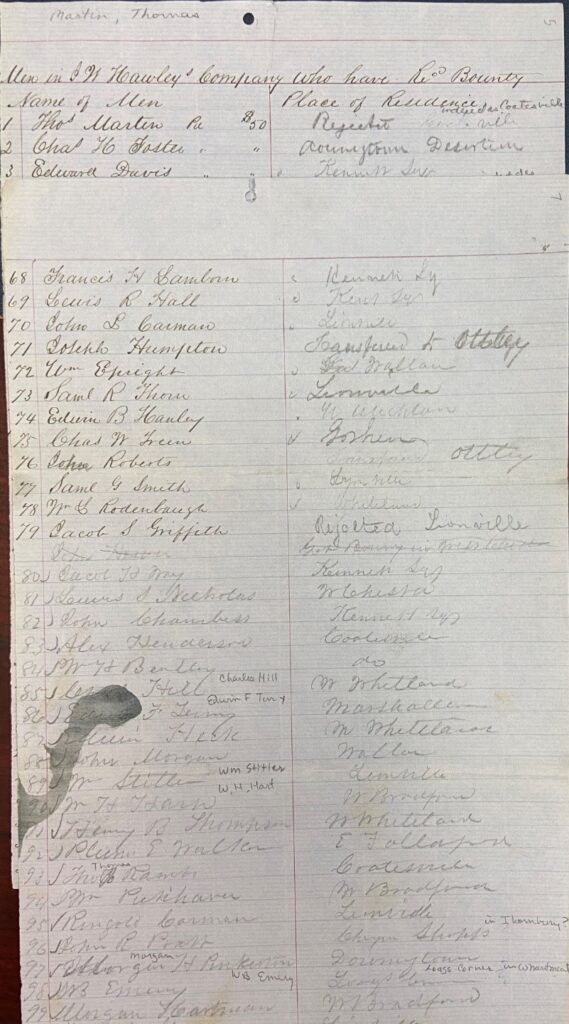

- Civil War Bounty Records, Chester County Archives

- Photo of G.A.R. members, CCHC, General Photos, Military Organ., G.A.R., McCall Post #31

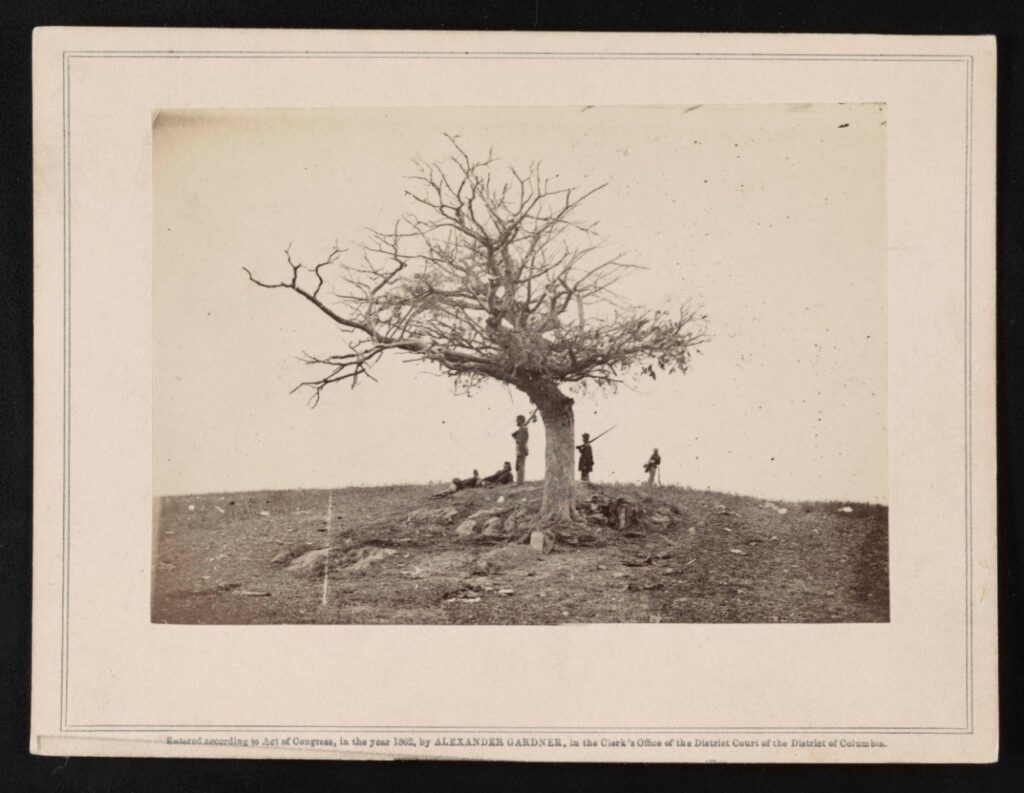

- Photo of grave at Antietam, LC, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2014646938/

- Recruitment poster, CCHC, Broadsides, Military, Civil War

- Photo of Mary Quantrill, Scrap Book, July 1908, page 110

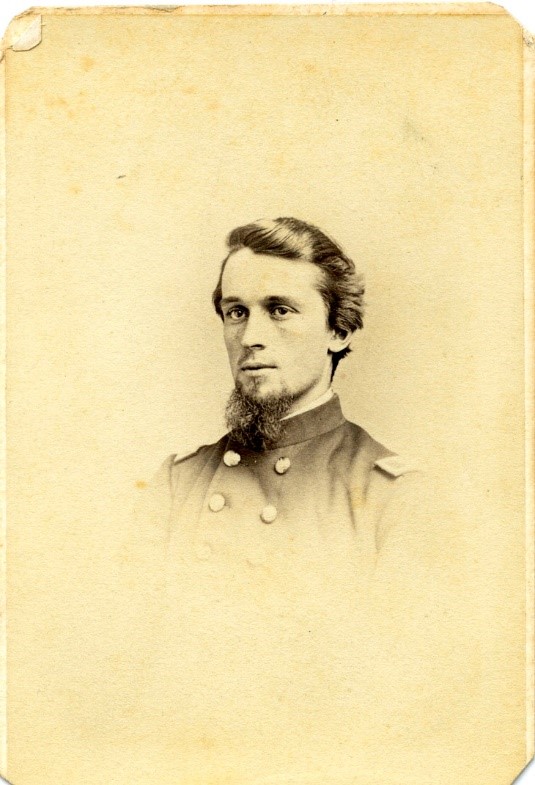

- Photo of Joseph W. Hawley, CCHC, CDV 783

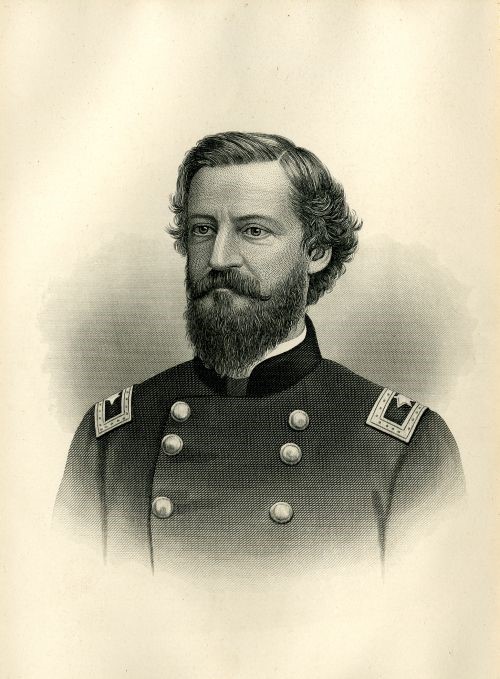

- Photo of Thomas L. Kane, History of the Bucktails, 1906

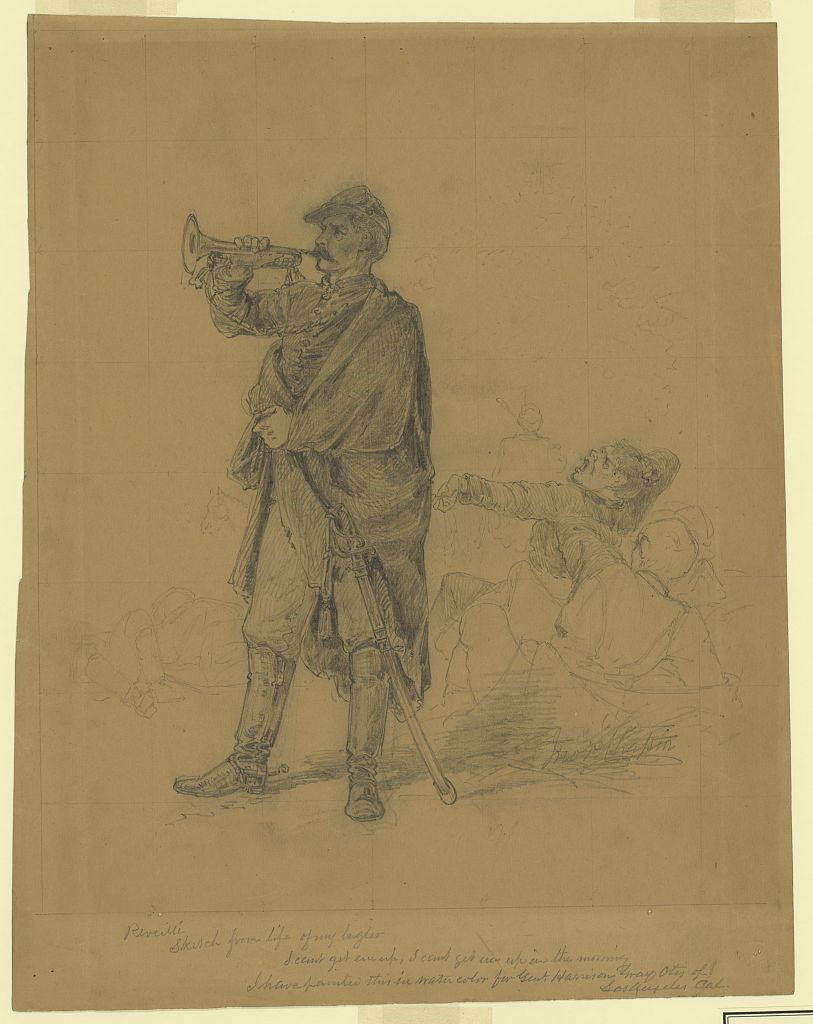

- Pencil sketch, Civil War bugler, LC, https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.21782/

10-11. Photos of Dunker Church, Antietam, CCHC, DN10

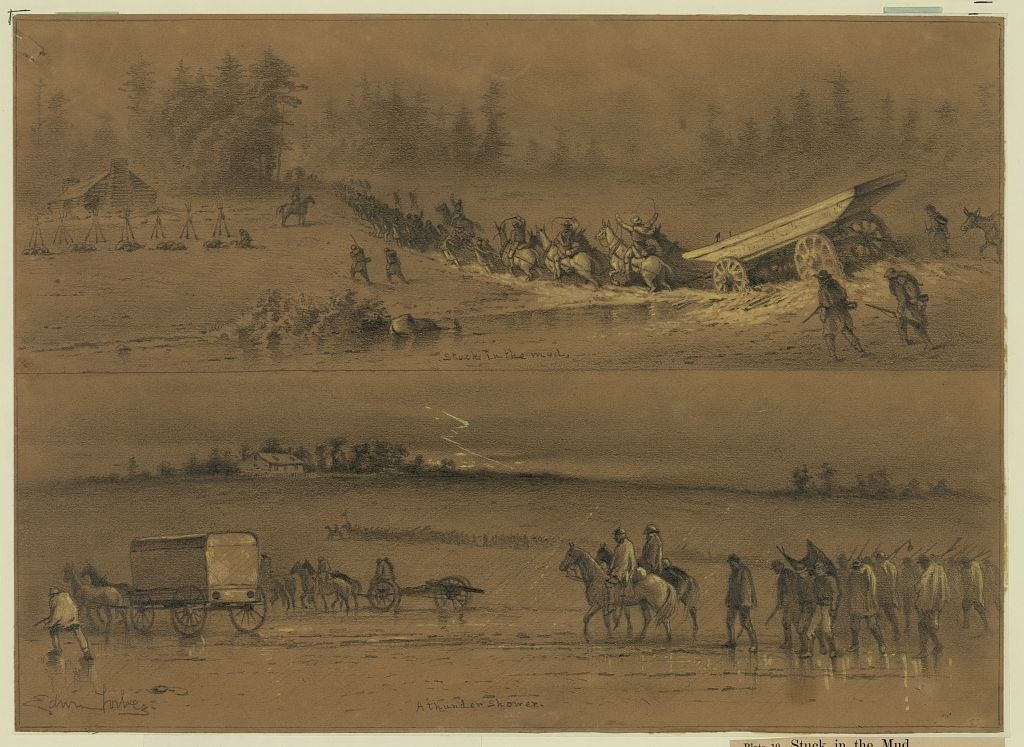

- Drawing of Mud March, LC, https://www.loc.gov/item/2004661529/

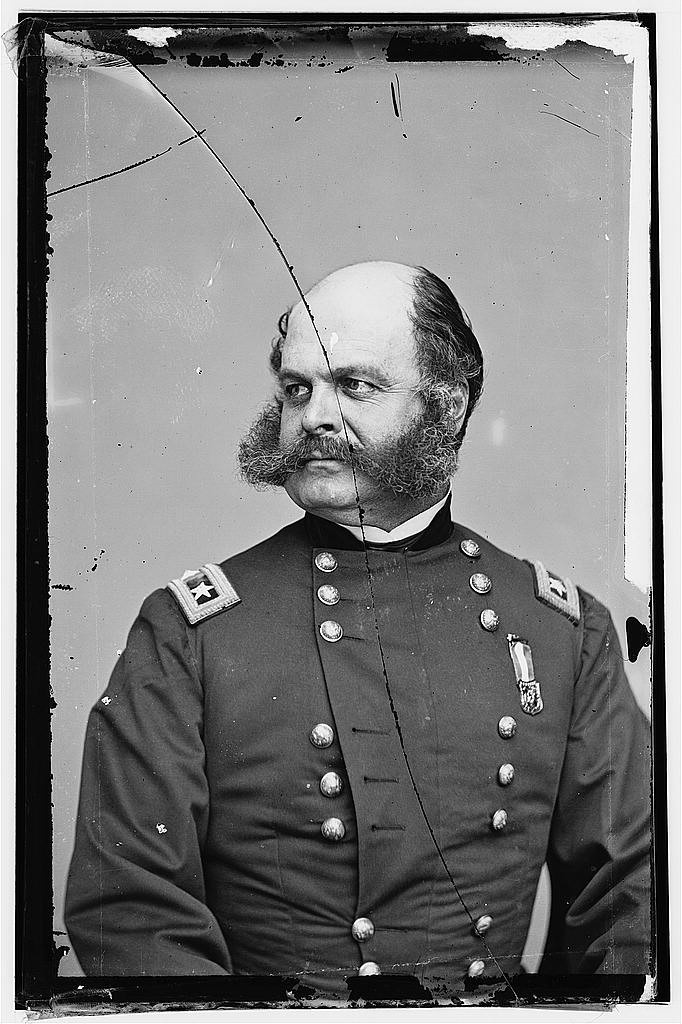

- Photo of Ambrose Burnside, LC, https://www.loc.gov/item/2018668336/

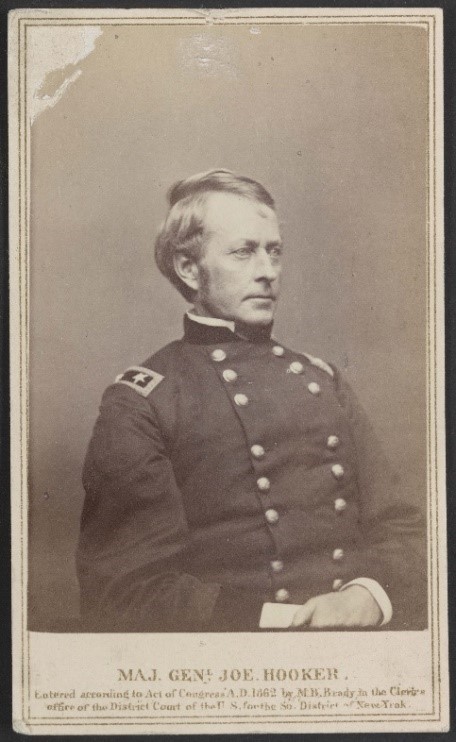

- Photo of Joseph Hooker, LC, https://www.loc.gov/item/2012647054/

- Pencil sketch, Civil War dispatch bearer, LC, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004661053/

- Map of Chancellorsville, LC, https://www.loc.gov/item/gvhs01.vhs00224/

- Pencil sketch, Chancellorsville moonlight march, LC, https://www.loc.gov/item/2004661813/

- Photo of Aquia Creek hospital, LC, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2018672359/

- Photo of G.A.R. Memorial Hall, , CCHC, General Photos, Military Organ., G.A.R., McCall Post #31

- 124th Bucktails Reunion Program, 1898, MS Coll 181, Box 1, Folder 3

- Recruitment poster, Kane, History of the Bucktails, 1906

- Photo of Thomas B. Winslow, cap with bucktail, LC, https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.75400/

- Photo of site of Charles Frederick Taylor’s death, CCHC, Stereographs, W.H. Tipton, #520

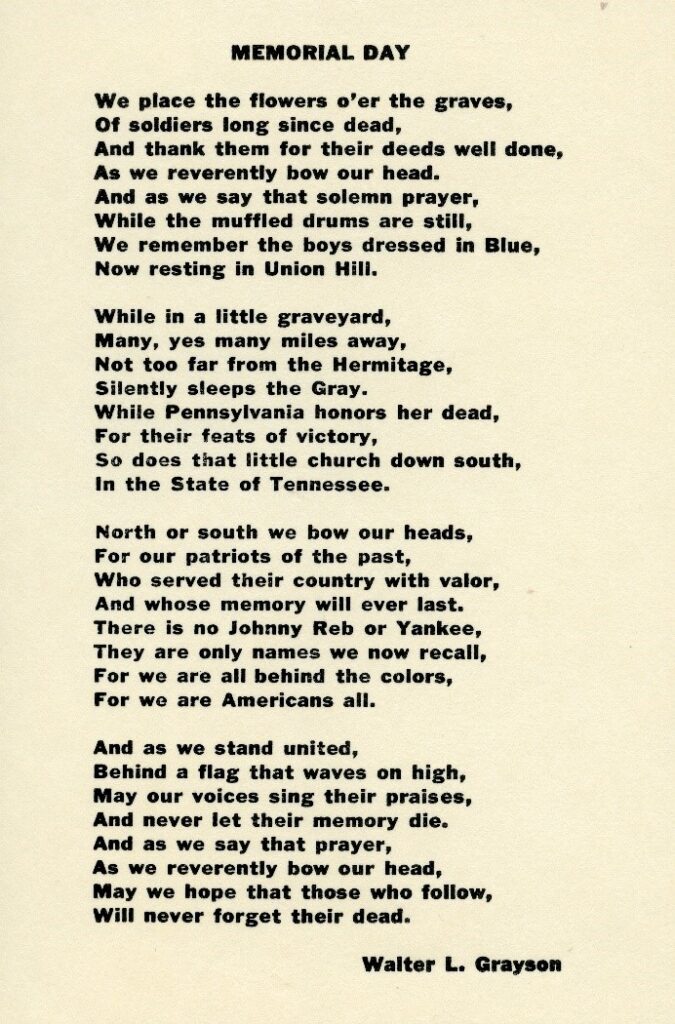

- Poem by Walter L. Grayson, “Memorial Day,” CCHC Civil War Collection, MS Coll 181, Box 1, Folder 3

See also:

- Civil War Collection, MS Coll 181

- Includes manuscripts and printed material relating to the 124th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment

- Hawley Family papers, MS Coll 184

- Includes correspondence to the Hawley family re. Col. Hawley’s wound, including letters from Joseph to his family

- Bayard Taylor and Taylor Family Papers, MS Coll 237

- Includes correspondence and manuscript material relating to the Taylor family during the Civil War