Battle of Brandywine Memory

by Wyatt Young, Librarian

No matter how long you’ve been in Chester County, whether it’s as a visitor for one day, or a lifelong resident, its a good chance that at some point you’ve probably encountered mention of the Battle of Brandywine. It’s become part of the fabric of Chester County’s identity, and for the past 247 years it has been the subject of artwork, scholarship, commemoration, and reflection.

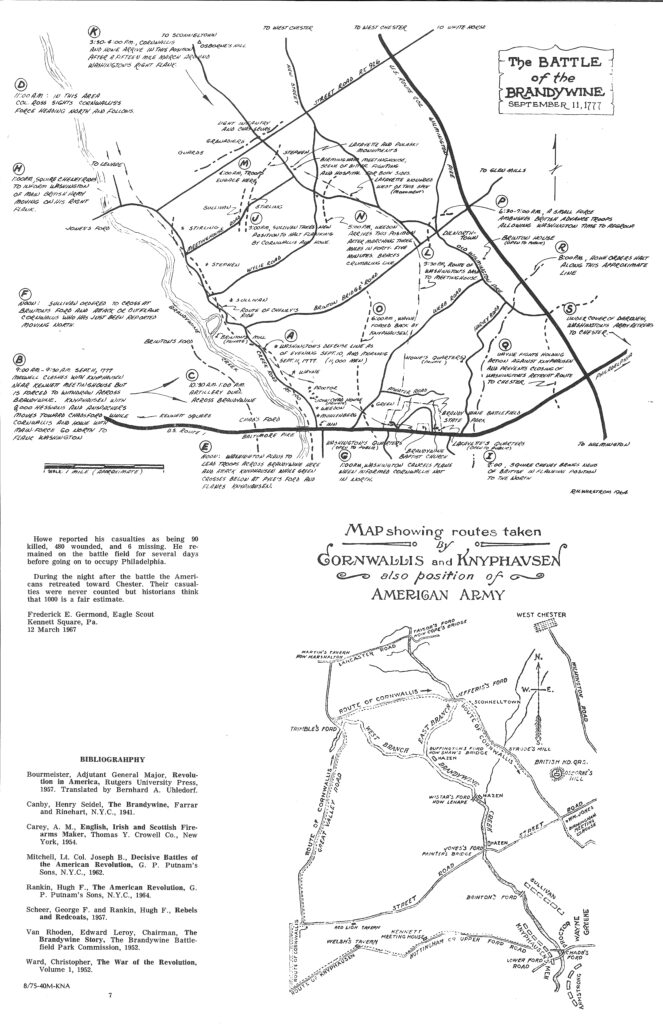

For those who may not yet be familiar, the Battle of Brandywine occurred on September 11, 1777 and was a key event that marked a turning point during the American Revolutionary War. General George Washington’s troops faced a tough defeat when British forces, led by General William Howe, outmaneuvered and overwhelmed them, opening a path to the capture of Philadelphia. Despite the setback, Washington’s army regrouped quickly and fought on, with this battle serving as a crucial learning experience. The Battle of Brandywine also saw key figures like General Lafayette rise to prominence in our historical memory of the American Revolutionary era.

As a historian, one thing I’m intrigued by is how our historical memory of events like the Battle of Brandywine is shaped and develops over the years. Historical memory refers to the collective way that cultures and societies remember and interact with the past. In our current era, we often have the tendency to think of history as static, set-in-stone facts that never change. But in fact, history is anything but. It’s more of an iterative process. It’s something that we practice through the commemoration of events, the erection of monuments, and creation of historical lessons. Throughout this process, we constantly adjust our interpretations of history by using newly discovered evidence and sources to further shape our understanding.

For an example of what I mean, let’s think about the way we remember the Wright Brothers’ first powered flight. Originally, you might have been taught a history that solely relied upon their groundbreaking achievement in 1903, celebrating them as aviation pioneers. While this is still true, over the years this narrative has broadened to recognize the contributions of earlier inventors and engineers who played a key role in advancing aviation technology. Today their success is often seen as part of a larger story of innovation, rather than a singular moment in history. This does not diminish the achievement of the Wright Brothers, rather it expands our understanding of the world in which they were operating.

As we look back into the history of the Battle of Brandywine, one useful exercise that can expand our understanding is to track how the memory and interpretation of the event developed over time. In some of the earliest writings we have here at CCHC, it’s clear that there was an emotional and patriotic connection held by Chester County residents. In the early 19th century, one of the ways this was accomplished was very similar to how we reflect today: by gathering and commemorating historic events with guest speakers.

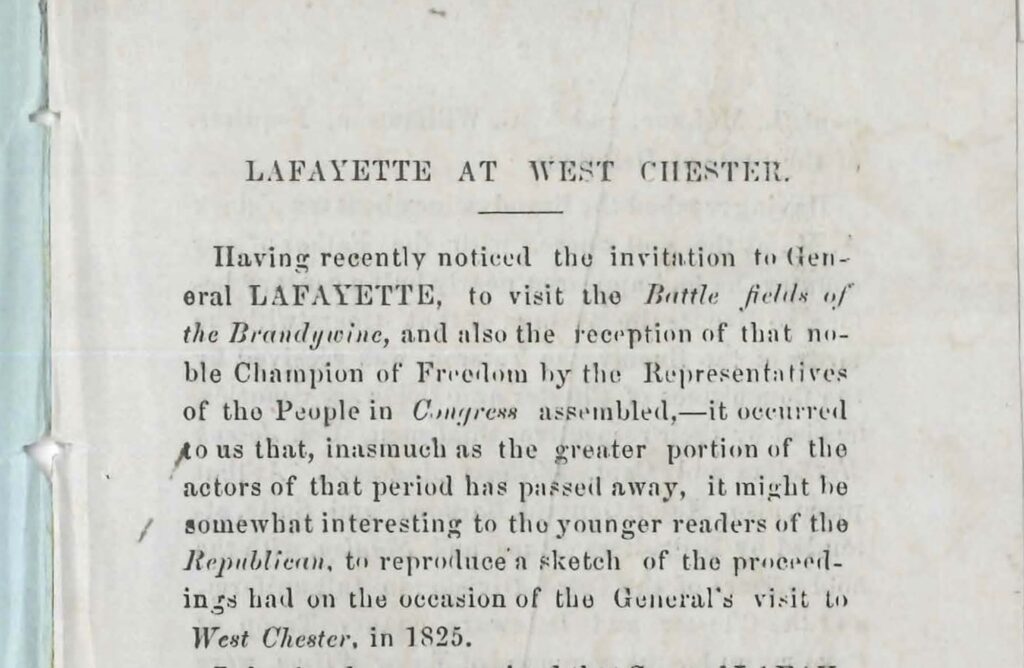

In 1825 Lafayette returned to the U.S. nearly 50 years after the war as part of a tour retracing his Revolutionary steps and recalling his experiences. This tour helped cement Lafayette’s place in American memory, and during his stop here in Chester County, he was celebrated as a living symbol of liberty and was greeted with parades, toasts, and speeches. He was often connected in these discussions to Washington and other prominent figures such as General Anthony Wayne, another local Chester County hero. During this time, the media often framed Lafayette’s role in the battle not only as one of military importance, but also as one of divine purpose and moral struggle. He was compared to the biblical story of Moses leading the Israelites, helping to place both he and the Revolution into a more spiritual context. There was also quite a bit of discussion surrounding the enduring friendship between the U.S. and France.

These speeches and commemorations during Lafayette’s visit helped lay the foundations for our current historical memory of the Battle of Brandywine. As we can see in 1825, the battle was primarily discussed as one of heroic sacrifice and valor, with less emphasis being placed on defeat. Judging from the articles published at the time, it was clear that a message of resilience would be a fixture of discussion surrounding the battle.

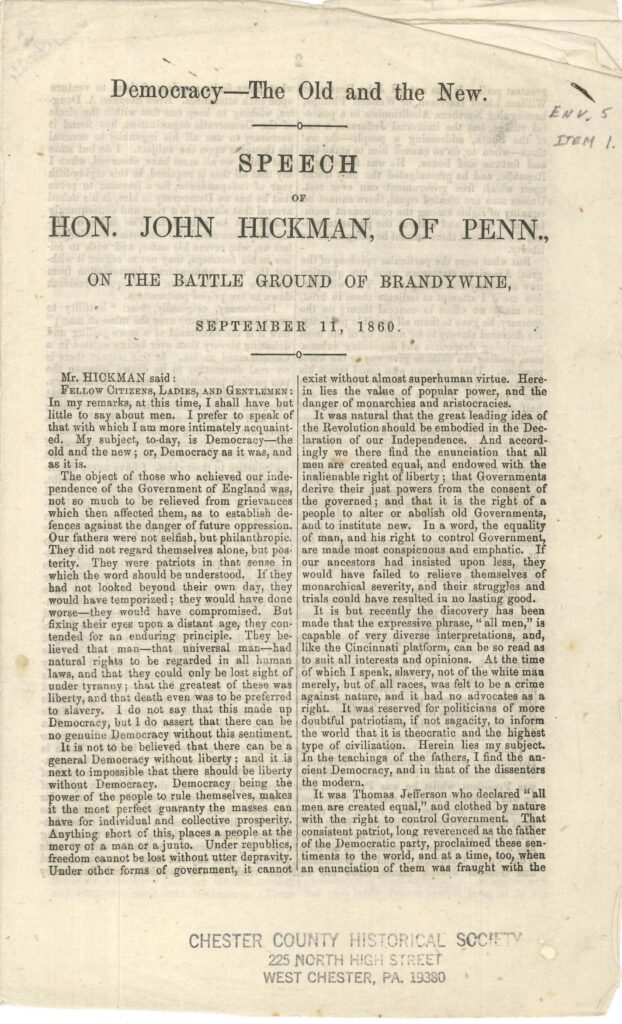

Looking forward to 1860, we see a United States upon the verge of the Civil War. It was a time of great upheaval in our region, and it is during this moment that we see the Battle of the Brandywine leveraged to address the turmoil. In a speech made by Pennsylvania House Representative Jonathan Hickman, the established memory of the battle’s moral struggle was used to reflect upon the tensions of the day. In Hickman’s address, he drew parallels between the Revolutionary War and the growing conflict over slavery, emphasizing that the liberty and democracy fought for at the Brandywine was being threatened by pro-slavery sentiments. For Hickman and other Chester County residents of the day, the Battle of the Brandywine had clearly become a symbol that resonated in the public square and served as an anchor point for moral discussion.

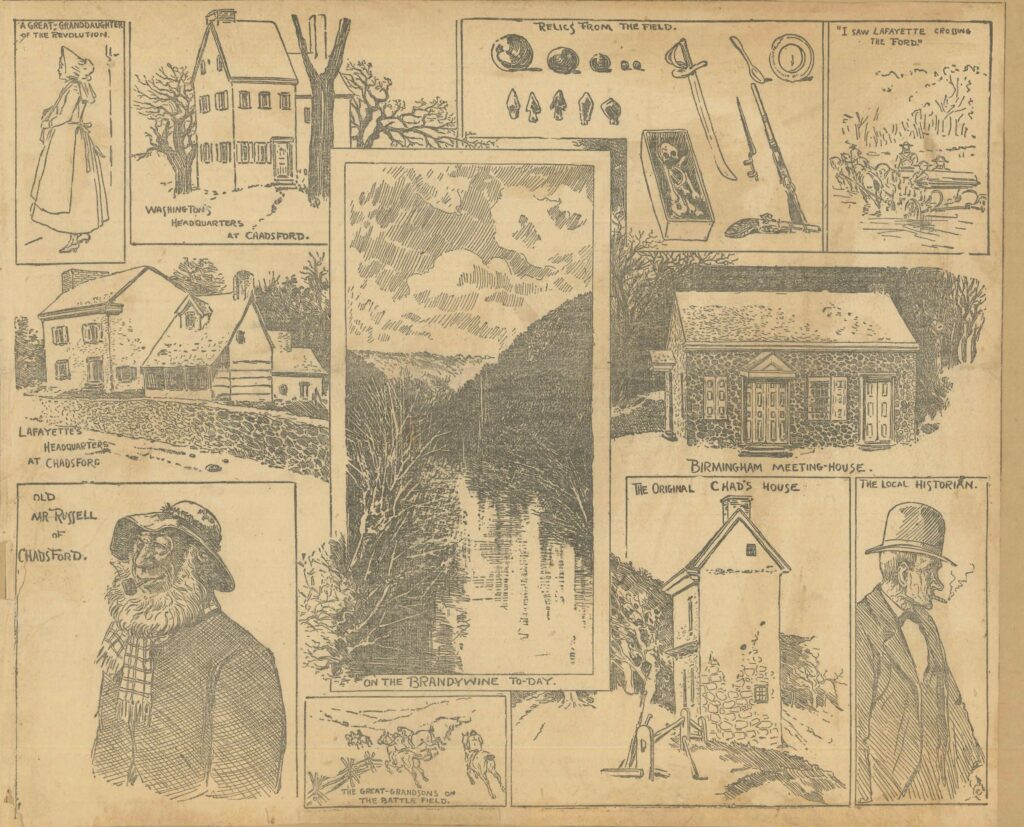

By the 1890s, memory surrounding the Battle of Brandywine had become more locally focused with emphasis placed upon oral traditions passed down by families in Brandywine Valley. This perhaps can be seen as a need to form bonds of community during the Gilded Age, a period of economic and population growth in American history that deepened social and class divides. During this time, history was often used as a method to assuage fears and validate identities. The local memories of the Battle of Brandywine helped provide a more intimate portrait of the battle, connecting it not just to the larger national narrative but also to the personal lives of its community members. It is through this combination of oral tradition and personal attachment that we sometimes see historical fact blended with local lore, particularly in these 1895 articles recounting the battle.

In this series of articles, anecdotes such as Washington’s ride through the countryside in order to reposition his troops was told in an informal and more entertaining manner. There was also much discussion concerning the relics and physical remnants of the battle, such as musket balls and cannonballs found in the area. These artifacts served as tangible connections to the past, ensuring that the memory of Brandywine lived on not only in public commemorations but in the everyday lives of the local population. The battle was portrayed as a sacred moment in the community’s history, one that continued to shape local identity well into the late 19th century.

As Chester County entered the 20th century, the commemorative tone surrounding the Battle of Brandywine began to shift once more. In 1915, the U.S. was on the cusp of entering World War I. Much of Europe had already been at war for nearly a year at this time, and anxieties around American involvement was growing. In addition, thanks in part to the Antiquities Act of 1906, this was also a time when the U.S. was consciously expanding its monuments and parks systems across state and federal levels. With these contexts in mind, it is no wonder that the uncertainty brought about by possible war would be a moment in which the U.S. would seek to reflect upon its past.

In 1915, a series of events was held at the Battle of Brandywine site by the Pennsylvania Historical Commission and multiple historical societies to mark and preserve the location. In our collections here at CCHC, we hold several programs of this commemoration wherein great importance was placed upon remembrance and marking the land where the battle took place.

Perhaps the interpretation used by Hickman in 1860 to reflect upon social injustices helped lend itself to a more inclusive tone, as newer additions to the historical memory were also being expanded. In reading the program from 1915, we can see there were leanings towards what we would today consider be more socially inclusive interpretations. Attention at the ceremony was given not only to famous figures like Washington and Lafayette, but also to the women of the Revolution, whose significant contributions were spoken about by the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Also interesting about this time is that was the inclusion of an international dimension to the event. In a similar manner to how the friendship between the U.S. and France was emphasized during Lafayette’s visit of 1825, the 1915 commemorations also highlighted the importance of global alliances. Perhaps as a moment of foreshadowing, the alliances between the U.S., France, and Britain were discussed at the commemoration. And by 1917 the U.S. would enter the fray of WWI alongside these very alliances.

Another addition to the historical memory that was present during 1915 discussion was the broader acknowledgment of how the battlefield itself had changed, moving from a site of military conflict to one of peaceful agriculture and memorialization. The juxtaposition of the old battlefields with their new, peaceful purposes reflects a historical progression in the way the battle was remembered as a place of enduring historical significance. It also aligned with the push to preserve and commemorate sites across the country as part of our national and local heritage. But by the time of World War II, emphasis upon the patriotic sacrifice and the importance of military decisions during the Battle of the Brandywine would once again take center stage.

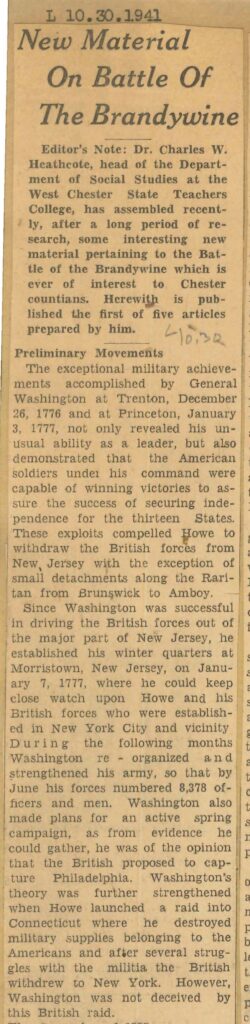

In 1941, with the U.S. on the brink of war once again, Chester County historian Charles W. Heathcote wrote detailed accountings of the Battle of Brandywine which emphasized military strategies. Heathcote framed Washington and his generals as steadfast and competent leaders in the face of defeat. In this interpretation, we see the narrative of how a military loss could ultimately inform future victories, cemented by lessons learned through strength and resilience. This message would soon reflect how the U.S. sought to project its own strength and resolve during the World War II era and beyond.

But Heathcote’s interpretation doesn’t just stick to an easily digestible narrative of American dominance. He also also revisited controversies of the Battle of Brandywine, particularly those regarding General John Sullivan, whose role in the American defeat was the subject of much debate and was rarely mentioned in earlier celebratory interpretations. In this account, Heathcote defends Sullivan, providing a more nuanced understanding of the internal divisions within the Continental Army. Overall, Heathcote’s interpretation of the Battle of Brandywine was one of endurance and tactical growth, with complicated parallels drawn to the broader resilience of the American spirit in times of adversity.

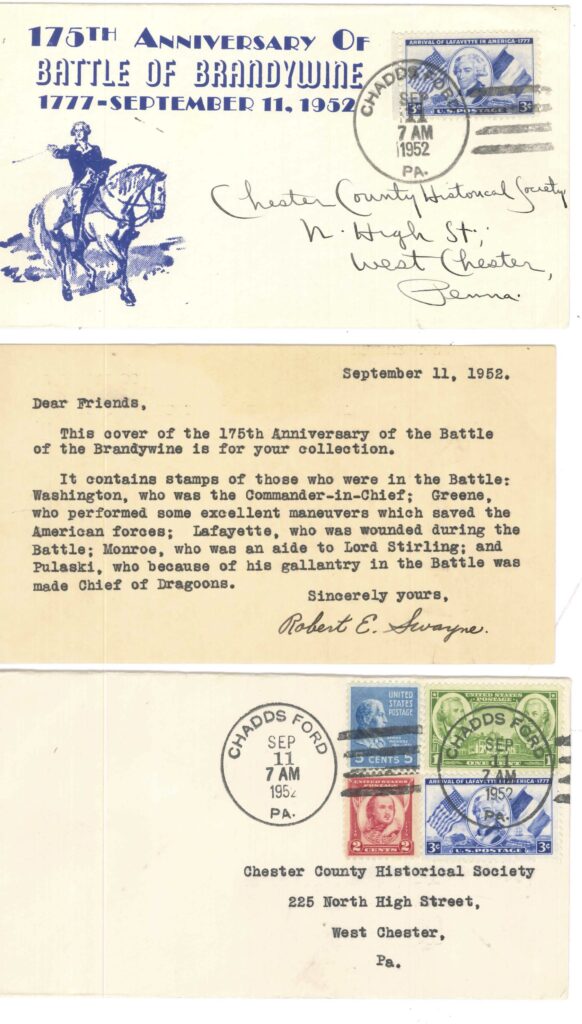

By the time of the 175th anniversary in 1952, the Battle of Brandywine was firmly embedded as a hallmark of both Chester County and American pride. The commemorations of that year emphasized the expected heroic figures of the battle—Washington, Lafayette, Nathanael Greene, and others. Ina post-World War II context, memory of the event saw the battle remembered through the lens of American leadership and sacrifice, reflecting the Cold War era’s focus on national unity and the virtues of American democracy. Lafayette, in particular, was once again celebrated as a symbol of the international alliances that had shaped America’s path to independence, much like the strategic alliances America was forming during the Cold War.

By exploring the historical memory of the Battle of Brandywine throughout the years, we can see how it has evolved to fit our identity and needs. From the spiritual and moral victory interpretation of the early 19th century, to its use as a symbol of Union preservation in the Civil War era, to a need to form local connections and community during the Gilded Age, and finally to the patriotic commemoration of American resilience in the 20th century, the memory of Brandywine serves as a reflection of the cultural and political contexts in which it is remembered. Each generation that looks back on the battle finds new meaning, reshaping the narrative to fit their understanding of how Chester County fits into the larger contexts of American history and global events.

As we reach another anniversary of the Battle of Brandywine in 2024, I cannot help but wonder how historians of the future will view our contemporary interpretations. How do you think your understanding of the battle will differ from those of future generations? Only time will tell. But one thing is certain: we will no doubt make use of the Battle of the Brandywine in order to better understand ourselves and the world around Chester County.

[All materials used to research this post can be found in the CCHC Battle of the Brandywine Collection, located here: https://mycchc.org/battle-of-the-brandywine/

For more on this collection or to view it yourself, please visit the CCHC Library during open hours or reach us at [email protected]]