By MacLaren Remy, Library Intern

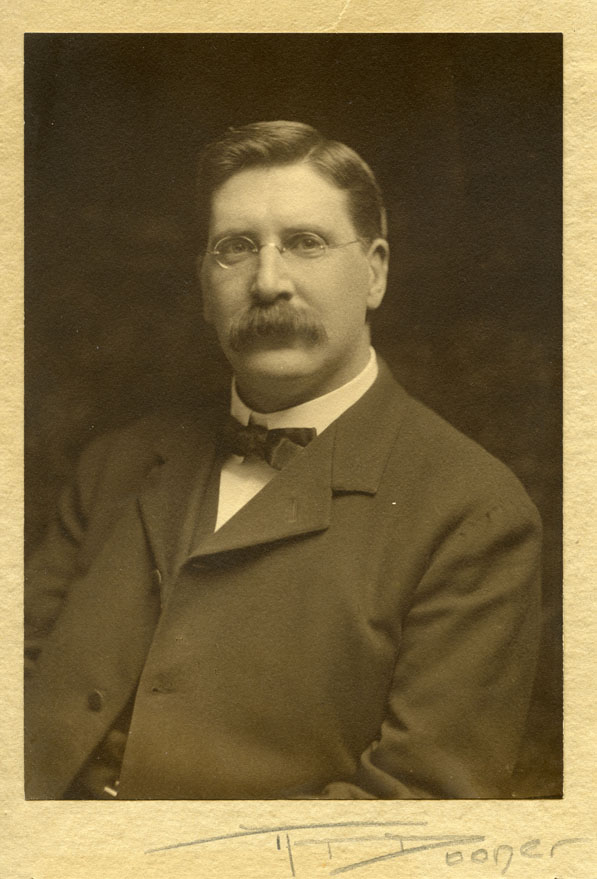

Thomas Lynch Montgomery (March 4, 1862- October 1, 1929) was a librarian, a historian, and an avid diarist. Montgomery was born in Philadelphia in 1862. He graduated from the University of Philadelphia in 1884, and even after his graduation, he remained involved with the school and his fraternity, Phi Kappa Sigma. Montgomery’s work was devoted to the various libraries he served and to preserving history. In 1886 he became a librarian with the Wagner Free Institute of Science. In 1892, he founded the first branch of the Philadelphia Free Library. In 1899, the Montgomery family rented a farm in Green Hill, Chester County. In 1903 when the diary collection began, Montgomery became the State Librarian for Pennsylvania, thus, splitting his time between Philadelphia and Harrisburg. In addition to his career, Montgomery was also devoted to his various clubs and societies. In his diaries, Montgomery primarily writes about his work, and many of the inserts relate to his social engagements.

Montgomery died of heart issues on October 1, 1929 at the University Club. He was 67. Susan survived him. Due to his participation with local historical societies and travels in Chester County, his diaries were donated to Chester County History Center, stipulating that they would not be opened until 1952.

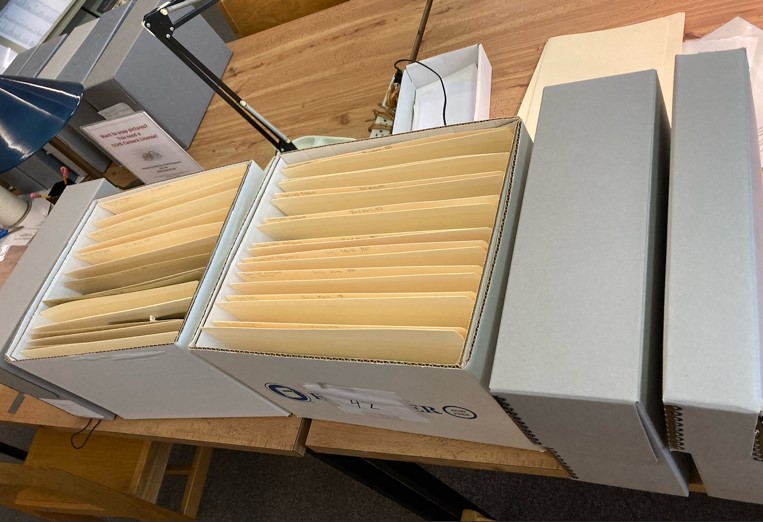

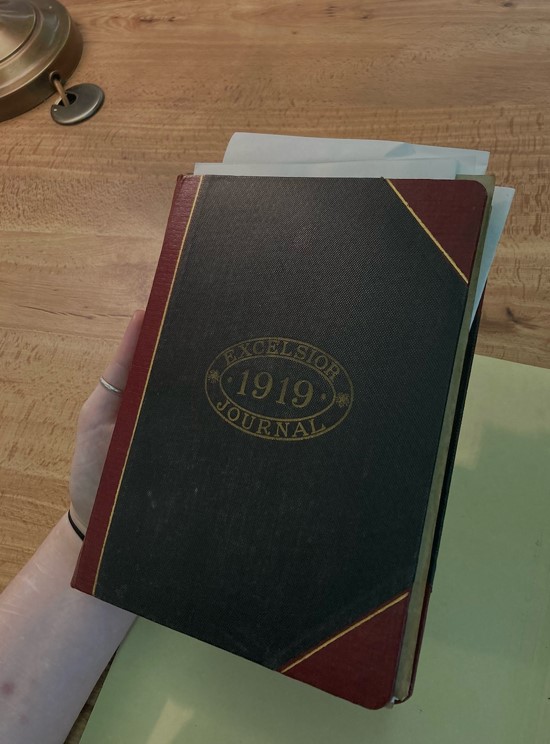

When the diaries were accessioned, they were stored ‘as is’ in archival boxes; however, with time, the ‘inserts’ Montgomery added began to stress the spines. The spines were bound to the diary pages and were not made to have 20-80 extra pages added. And so, I had to navigate how to maintain the original order of the pages and inserts while also preserving the structural integrity of the diaries themselves. So, first, I surveyed the diaries to ascertain the variety of inserts and to understand the relationship between the diaries and inserts. The inserts are primarily placed where they were received or when the related event occurred.

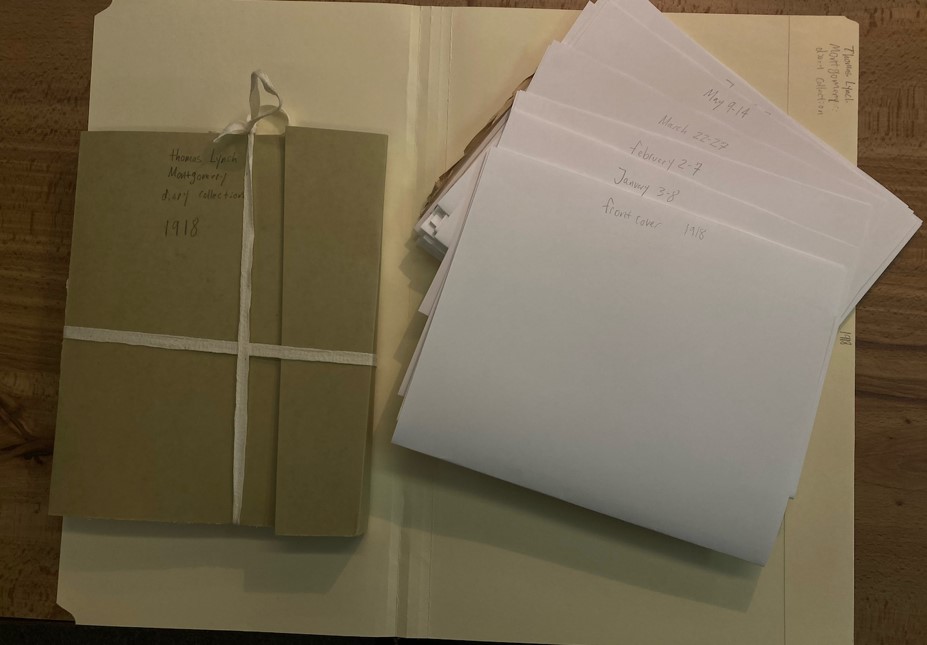

After the survey and a conversation weighing the various options with the librarian and overseer of this project, Judy Ng, it was decided to remove the inserts and place them in sub-folders with the location in the original diary noted on the front of each sub-folder. Each diary worth of inserts is assigned a folder. Each insert is numbered, and there is a corresponding index to preserve the original order and add navigability to the collection.

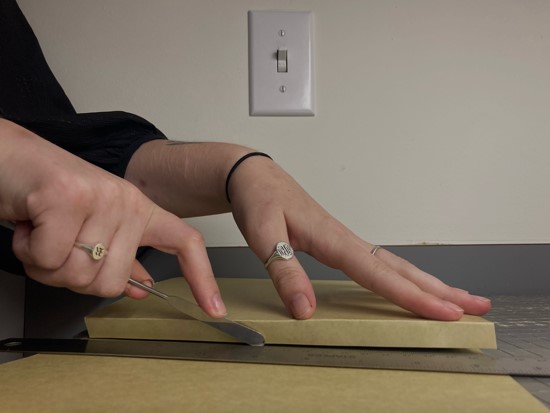

The now-emptied diaries also needed some attention; many of the spines have damage or red rot. Many of the spines were starting to flake off due to age. But more urgently, red rot had begun to affect the spines and decorative corner bindings. Essentially, red rot is the phenomenon when red leather begins to biodegrade, leaving the pigment behind in red chalky streaks. Red rot also can lead to flaking. And so, to protect the structure of the spines and prevent red rot from contaminating the inserts, I created cardstock enclosures for each diary by cutting cardstock to size. Then, I used a conservation spatula and ruler to create clean folds to fold around each diary perfectly, leaving each diary protected and the inserts organized.

Each unprocessed diary has now been split into two folders, the diary and diary insert. These folders, 42 in total, have been rehoused into 2.6 linear feet worth of boxes. Because they have been fully processed, these diaries are now ready for researchers to use and explore. The so-what of this processing project is simple; however, this task is important because it makes the diaries more accessible to researchers. The library is regularly processing and revisiting collections and is growing access to their primary sources, this being but one example of many.